The rise and fall of wework: It was the most valuable start-up in the United States, with plans to revolutionize how and where people around the world worked.

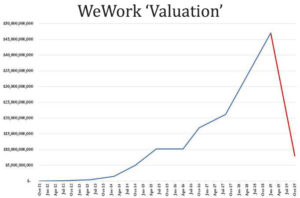

In less than one year, WeWork went from $47 billion to less than $8 billion.

The Beginning

The story of rise and fall of WeWork really starts with a man named Adam Neumann.

He was born in Israel. He moved to New York and majored in entrepreneurship and marketing. And he started all of these sort of fly-by-night entrepreneurial ideas like women’s high heels with collapsible heels. Another one was baby pants with kneepads on them to protect the babies’ knees for the crawling age.

Of course, the businesses were a tremendous failure.

So he settles on co-working. And in 2010, started WeWork.

The Rise of WeWork

WeWork is a leader in the business of renting out spaces to entrepreneurs. The company rents out a desk or a private office equipped with amenities like internet, coffee and spacious common areas.

They were sleek. They had community space, sofas all over the place for team-building. There was cold brew, taco Tuesdays. There was beer and wine on tap. Instead of going out for a drink, you’d stay at the office. It really came to symbolize the kind of start-up entrepreneurial hustle of millennials.

The thing Adam Neumann is really best at is communicating his vision, convincing people that he can change the way we work and live. He fully adopted the persona of the iconoclast start-up founder, and he looked the part. You know, at 6 foot 5, with flowing brown hair, you know, people looked up to him. When he walked into a meeting —people, literally paid attention to him. But the most important person who bought into his vision is a Japanese executive, the head of a company called SoftBank — Masayoshi Son. Everyone calls him Masa.

Masa’s company oversees something called the Vision Fund. This is the largest tech investment fund in the world. They have $100 billion dollars to play with, largely from the Saudis who want to diversify away from oil and invest in tech. And Masa is this very interesting character who’s always trusted his gut.

One of the investments he made is considered by many people to be the most successful investment in the history of mankind. Invested roughly $20 million in Alibaba. And at the time it went public, it was worth roughly $90 billion.

Adam Neumann gave Masa a tour of his offices. This includes the right soundtrack in the background and all the sleek office space and virtual-reality renderings of WeWork office space in the future. So you could wear these glasses and feel like you’re standing in Tokyo or Shanghai, right down to looking out the street and seeing the scene that you would see from the offices. And this really blows Masa’s mind. He loves this vision. He loves Adam’s energy.

After a 12-minute tour of the WeWork offices and Adam Newman’s vision — Masa Son invests over $4 billion in WeWork.

This is an enormous investment. And he doesn’t say, Adam, I need you to be a very careful steward of this extremely important investment. Be careful with my money. Instead he says, I need you to go crazier. I need you to do more. I need you to explore your wildest visions.

He started opening WeWorks all over the country. Every major American city had a WeWork. And then he expanded massively abroad. WeWork now is 45 million square feet of real estate. It’s the largest private landlord in New York, Washington, and London.

And then, giant companies started also moving their employees into WeWork offices, thinking it’s a draw for employees to work in these spaces, like, IBM, Verizon, Salesforce.

And this is the point when Adam really leans into Masa’s advice, which is to go wild. Pursue your craziest dreams. He opens a WeLive apartment building and wants to expand that. He was talking about WeGrow, and he and his wife opened a school in downtown Manhattan. There was WeBank, there was WeSail. There was WeSleep. There was talk of an airline. There was talk of WeMars, even putting office space on the red planet.

The Fall of WeWork

By and large, people looked at what Adam had accomplished, WeWork on every corner, taking over iconic buildings, and they believed in what he was selling. And then on top of that, you throw in Masa, this Japanese tycoon, who had made a fortune investing early on in these founders — Alibaba, Yahoo, Uber — just based on gut instincts. And if he believed in Adam, why shouldn’t everyone else?

WeWork does what successful start-ups do. They prepare to go public, meaning they can sell their shares to the public. There’s a valuation on the company of $47 billion. That makes it the most valuable start-up in the country. And part of going public, they have to disclose everything in paperwork. And that’s when things start to unravel.

So why did things start to unravel when WeWork files all this paperwork to go public?

This is the first time that journalists, investors, the public can really look under the hood at what’s going on at WeWork —

Do we have any numbers in terms of how much money they’re making or losing right now? — and it’s not pretty.

Net losses were just under a billion dollars, $904 million in the first half of 2019 alone.

They had rapidly expanded into markets that weren’t necessarily friendly to WeWork. And there had also been some kind of questionable financial dealings between Adam and the company that he started.

He had trademarked the word “We” and sold it back to the company for $5.9 million dollars. He ended up returning that money, but that certainly raised eyebrows. He had bought a lot of the buildings that WeWork was now leasing, so the company had paid him millions of dollars for space in the offices that he owned.

But then there’s the text of the I.P.O., the legal document that they filed with the S.E.C. The word “community” is listed more than 150 times. And there was all of this kind of propping up what we now know is a very unprofitable business with this lingo of self-help and creating community. And people just started to see it as selling air, you know, couching this unprofitable business in language that made people feel good. So this paperwork filed with the S.E.C. really sets off an implosion unlike any other in start-up history.

All the bad press and the bad moves caused the company’s expected valuation to drop from $47 billion down to just less than $8 billion

The value of WeWork plummets. So this is when discussion starts to spread of, well, should there even be an I.P.O.? Is this company ready to go public? And people start to turn on Adam pretty quickly at this point.

Eventually, Adam is forced to step down.

This house of cards was coming down, this business based on beanbags, distressed furniture, and Nespresso machines. And yet, somehow this guy’s been treated as some guru genius because he’s such an effective self-promoter

Where’d they get this $47 billion for $12 million in cash?

They decide that even getting rid of Adam does not save this effort to go public, and they have to pull the IPO. And this Japanese investor, Masa Son, who had been such a visionary, it’s extremely embarrassing for him. Ultimately, he has to apologize to investors, specifically for putting so much faith in Adam Neumann.

So what becomes of Adam Neumann at this point? He has been pushed out of his company. In a way, he has been exposed as someone who is a better salesman than operator of a company. And it becomes pretty clear that he has built something that is not all that revolutionary but is a little bit of a financial house of cards.

Conclusion

The story of rise and fall of WeWork and Adam Neumann is essentially a story of his exploitation of two phenomenon.

The first is this kind of late-stage tech capitalism, when investors really want to believe in these start-up founders who have businesses that are essentially sort of traditional businesses with tech layered on, and in turn, give these companies enormous valuations when the business underpinnings are not necessarily there. So the irony, of course, was that Adam Neumann tapped into this tech vernacular about changing the world, about revolutionizing office space, but his company had really nothing to do with tech. It was a commercial real estate company.

The first is this kind of late-stage tech capitalism, when investors really want to believe in these start-up founders who have businesses that are essentially sort of traditional businesses with tech layered on, and in turn, give these companies enormous valuations when the business underpinnings are not necessarily there. So the irony, of course, was that Adam Neumann tapped into this tech vernacular about changing the world, about revolutionizing office space, but his company had really nothing to do with tech. It was a commercial real estate company.

The second thing Adam Neumann quite brilliantly exploited was this yearning of millennials having this capitalist ambition and hustle, but also this yearning for community, this “we” generation, as he called it, that it’s not about you or me, it’s about we. And in the end, it essentially was about him.

The second thing Adam Neumann quite brilliantly exploited was this yearning of millennials having this capitalist ambition and hustle, but also this yearning for community, this “we” generation, as he called it, that it’s not about you or me, it’s about we. And in the end, it essentially was about him.

Note: For any information about Hierank MBA, feel free to disturb us, we are all ears for you CLICK HERE